The El Cap Report: Tom “Ansel” Evans

“Today’s El Cap Report….written just for you…unique in all the world!” Tom Evans would write in the El Cap Report. Those words whisked readers from their computers to Yosemite’s El Cap Bridge. There, cigar in mouth, Tom “Ansel” Evans would stand with a crew of bridge rats, dirty wall climbers drinking King Cobras, and his huge telescopes. The lot of them would point up at the Big Stone, plotting multi day ascents, slandering climbers who stayed on the wall too long, and explaining to tourons about how they use the bathroom up there. Starting in 2009, Evans entertained “cubicle pukes” across the world with nearly a thousand reports, over 7,000 photos, and countless stories of Yosemite’s 3,000 foot granite formation. From photo documenting the moon rise over El Cap, to detailing daily progress on the Dawn Wall ascent, to capturing Alex Honnold freesoloing past a guy in a unicorn onsie, to snapping photos of heroic YOSAR rescues, to showcasing the classic “Bail Of The Day,” Evans contributed to the climbing world in a way that allowed locals and the legends to transport on the wall, to check and make sure that El Cap was still there.

Born in Washington DC in 1944, Evans grew up in Arlington, Virginia. At 18, he marched off to the Virginia Military Institute, graduating with a degree in Civil Engineering and a position as an officer in the Army. He explored engineering work and an active duty position but found a career in public schools. “I quickly realized I liked teaching a lot more than engineering,” Evans said of his thirty year career teaching physics and math. He retired in 2003 and made his way to El Cap Meadow, where he’d been drawn as a climber.

At 13, young Tom picked up a copy of National Geographic. Sitting in his grandparents’ house in the rugged North Carolina mountains, he poured through the exploits of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hilary’s 1953 ascent. “I was immediately taken by the adventure, history, and romance of climbing and that was it,” Evans said. “I was to be a climber ever since.”

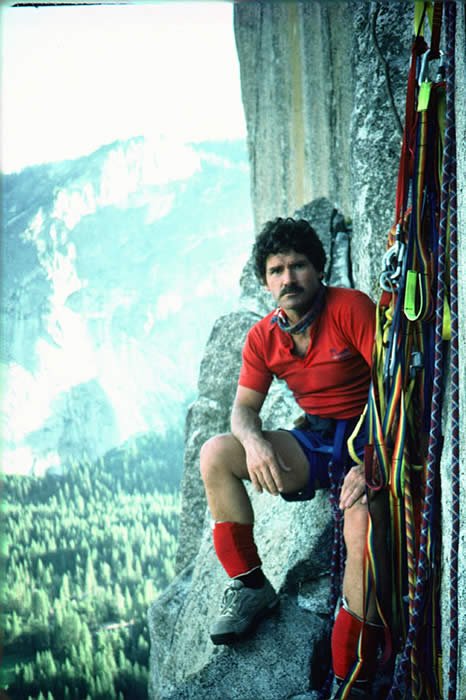

Evans started climbing on the Wissahickon Shist of Carderock, in Great Falls Virginia and on the Tuscarora quartzite of Seneca Rocks in West Virginia. The crystalized white quartz and the hard, sandstone-esque rock prepared him for a trip to Yosemite in 1967. The enormous granite walls inspired him. “I loved the great Valley and made a goal of climbing the Nose of E Cap,” Evans said. He returned in 1969 for a long season climbing the South Face of Washington’s Column, the North Face of Quarter Dome, and the North Face of Sentinel. After his successful wall climbing season, he and John Porter travelled to Chamonix to alpine climb. “We were caught in a storm and I got a bit of hypothermia that convinced me I really didn’t like to be in high, cold mountain environments,” Evans said. “I decided that Yosemite was to be my main climbing interest.” In 1971, Evans and Paul Sibley climbed the Nose. In 1987, Evans moved to southern California, climbing in Joshua Tree, Tahquitz, and making numerous trips to Yosemite, where he continued to climb on El Cap.

Though Evans continued to climb, his interest in photography increased, a hobby he’d had since high school. In 1995, after seeing a Glen Denny shot of climbers on Half Dome, Evans bought a telephoto lens and small camera and hiked into the Yosemite woods. He spent hours photographing the climbers on El Cap. “It was within easy distance from the road and had great lighting,” Evans said of his time obsessing over the formation. “I also had a great love for that old rock and the history of climbing on it.”

Evans faced a steep photographic learning curve. “My first attempts were miserable failures as I had no real idea of what I was doing,” said Evans. He received advice from climbing photographers, invested in better equipment, and kept working at it. He took colored slides and processed them. “It was a huge pain but I got organized and made it work.” In 2006, Evans transitioned into digital cameras and better telephoto lenses, namely a Nikon D5600 body and an old auto focus A1 600mm lens. “I was getting what I had always wanted,” Evans said, “Good, clear shots from a distance.”

As Evans photography improved, he moved from the woods onto the El Cap Bridge to be closer to his van and safely transport his equipment. Climbers gathered nearby to rack up, to ask Evans about other parties on the wall, and to scope their friends progress on the wall. Hoping that he’d be left alone by the barrage of wall rats, Evans bought a separate telescope so climbers could scan the wall for themselves. “But my friends wanted me to tell them everything that was going on and when new people showed up they wanted me to tell them too,” Evans said, “so I was talking all day long!” To cut down on the jabbering, Evans started The El Cap Report, which he described as light entertainment for climbers, which included accurate climbing information and a bit of slander. “A small portion of what is written is sometimes simply a fabrication, written to make the story ‘better,’” Evans writes on the El Cap Report Home Page. “Don’t take this stuff too seriously.”

The report became popular, averaging 8,000 reads a post with the documentation of Honnold’s free solo on The Freerider reaching 400,000. Readers scrolled the pages to not just read about the celebrity ascents but to hear about their friends on the wall. Evans made a commitment to documenting all the action on El Cap. “The other photographers didn’t want to bother with the common climber, as there was no money or magazine glory to be had from them,” Evans said. “I just liked to shoot and most of the “common climbers” were friends of mine anyway, and they would sometimes give me a few bucks to help with lunch or gas.” Evans self-funded his photography and the El Cap Report. “Most climbers have little money for anything but survival and gear so many never contributed and I just gave them the shots anyway,” Evans said. “It has never come close to meeting even the most basic expenses and 99% of the readers have never donated a dime for its upkeep,” Evans said. “Those who have donated hold a special place in my heart and I personally write each and every person a personal note of thanks.”

To help support his documentation Evans’ time at the Bridge, the Yosemite Climbing Association’s developed the “Ask a Climber Program,” which gave tourists close access to a climber, Evans, who could answer the pertinent questions like, “How do they sleep up there?” and “Where do they use the bathroom?” The program helped to ease relations between climbers and the National Service, which had been openly hostile to climbers and now seeks to both promote climbing and more closely regulate it. While NPS wanted to support the Ask A Climber program, they also wanted to sensor the El Cap report and own the rights to Evan’s photos. Evans quit immediately while NPS continued the program with government employees.

In the early 2000s, El Cap boomed with activity with new hard aid lines, fast ascents, and new free routes being established. The flurry died down though diehards like Evans remained. “I felt, early on, that El Cap had slipped into the backwater of big time climbing and the mags only covered it once a year or so,” Evans said. “I wanted ElCap to return to a position of prominence it had in the 60s and felt my report could provide the stimulus for that to happen.” It did just that.

At 79 years old, Evans has decided to step away from the El Cap Report. The time, energy, and financial commitment drained him. Evans said of his years long obsession, “I want to have more free time to stay in the meadow late into the evening to enjoy the warm lighting on the cliff.” October 17th marked the end of the El Cap Report with its stories, its weather reports, and its straight shooter charm. “It is my gift to you,” Evans said of the report, “and hopefully will be there for many years to come.” While the regular El Cap reports will be missed, for those that dream of El Cap, who froth in the meadow, and who feel the call of granite adventures, the stories remain. They’ll be there to transport the reader back to the bridge, and Tom Evans standing beside a telescope, smoking a cigar, and pointing at the wall.