Fall of Man

In the spring of 1988, Salt Lake City climbers Boone Speed and Jeff Pedersen drove through Arizona’s Virgin River Gorge (VRG) on a tip from a BLM-employed friend who had praised the velvety gray limestone he had seen there. “It’s like the French rock in the magazine,” he told Speed, who, with Pedersen, had just started developing the limestone of American Fork, Utah, and putting up some of the hardest routes in the U.S. to date. Upon first glance, the VRG cliffs were small and somewhat unimpressive, but it was enough to keep them exploring. After finding orange limestone—unlike the solid gray European stone that was promised—they pulled over on the busy thoroughfare of I-15.

Alex Honnold working Necessary Evil (5.14c) at the VRG

We walked up to [what is now] Blasphemy Wall and just freaked out,” said Speed. Pointing to an obvious and beautiful line, Speed declared, “I’m gonna do that.” The first route at the VRG, Fall of Man, goes through steep terrain with a series of pockets and small edges that lead into a technical slab. When he sent the route in 1990, Speed conservatively rated it 5.13a. It was a 12d to a 5.11 slab. “Back then it was bolted exactly the way everything else in the world was bolted,” he said.

Though power drills came to the United States in 1987, most sport routes at the time were drilled by hand, requiring 30 minutes to place each bolt. Developers placed little protection due to the physical toil of hand drilling. Speed and others bought power drills during the early days of VRG development, but the ethic of sparse bolting remained.

“Being bold used to be a lot about what climbing was,” said Randy Leavitt, who also established many of the routes at the VRG, including Joe Six Pack (5.13a), Captain Fantastic (5.13c), and Horse Latitude (5.14a). “In the ’90s, we all still felt that; that was still part of our upbringing.” Climbers have since upgraded Fall of Man, calling it solid 5.13b.

The unclipped draw 50 feet up on Fall of Man teased my waist. Wrapping my thumb around my fingers into a full crimp, I threw to a good left-hand edge—and missed. Screaming for 30 feet, I passed the unclipped draw as my shriek blended in with the roaring sound of the semis on the highway below. In December 2015 I met Alex Honnold at VRG to climb for a few weeks. I was stronger than ever, having spent the fall bouldering in Yosemite and sport climbing at Jailhouse in the Sierra foothills. Feeling fit and confident, I knew that now would be a good time to work my weaknesses, so I headed to the VRG for good winter climbing conditions and to test my footwork and crimping skills on these old-school routes.

My Saturn Station Wagon parked in the Joshua Trees during a rest day from the Fall of Man

The technical style, mandatory commitment, and overall headiness of Fall of Man make it an American classic, and an ideal project for me. After finishing the VRG’s first route in 1990, Speed rapped down to the right of it. “Oh yeah, this will probably be 5.13a or something,” he thought to himself.

“It’s harder than that—I was mistaken,” he said 26 years later. Without realizing it, he bolted the hardest route in the country at the time, Necessary Evil (5.14c). “That was kind of the culmination of the [idea that the] hardest routes have the smallest holds.” It was the mindset of the era, but back in Salt Lake City, Speed and Pedersen were establishing steep routes in the Hell Cave of American Fork at the same time they were establishing techy crimp lines at the VRG. “With steeper climbing came more holds. You could hold on to shit, and it became more of a [gymnastic] sport that’s also now being fostered by the indoor climbing scene,” said Speed.

Adrian Ballinger logging some air time on Fall of Man (5.13b)

Necessary Evil was first climbed in 1997 by Chris Sharma, and in the almost 20 years since the first ascent, it’s only seen a dozen repeats by some of the best climbers in the world. In 2015, Adam Ondra climbed the route in 45 minutes, slipping at the start, then falling at the redpoint crux, and sending on his third try. He called it one of the best routes in the world at the grade. Despite the accolades and the easy access 100 yards from a major highway, it’s had relatively few ascents when compared to other highly repeated lines like Golden Ticket (5.14c) or Lucifer (5.14c), both in the Red River Gorge, Kentucky, or Joe Blau (5.14c) in Oliana, Spain. All of which were established a decade or two later and have seen seven, 10, and 16 ascents, respectively.

“Necessary Evil has really hard footwork, small holds, and is mentally difficult,” said pro climber Jonathan Siegrist, who climbed the route in 2011. “It’s not the type of skill or strength you can develop in a gym.”

“Wanne climb in the sun?” Honnold asked while staring at Necessary Evil for a minute before grabbing his backpack. It was New Year’s Eve, and three weeks of manic crimping on the limestone, the cold weather, and the roar of the semis on the nearby highway had crushed his spirits. He’d climbed from the ground to the redpoint crux four times. BJ Tilden, a 35-year-old carpenter from Wyoming and an unsung hero of American sport climbing, had tried the route with Honnold and gave him the beta, but the hard moves at mid-height—grabbing a small pinch and falling into a slot—had defeated both climbers.

The south-facing Sun Cave sat just across the Virgin River, offering our numb tips and cold attitudes some warmth. We tyroled across the river and found Sunburst (5.12c), an amazing bolted tufa established by Bill Ohran. In typical Honnold fashion, he onsighted Boyle’s Route (5.13a) then flashed Sunburst. Whereas the Blasphemy Wall was cold, unforgiving, and terrifying, the Sun Cave offered friendly and safe climbing. It resembled the new-school style of climbing. The tufa holds, although steep, felt easier to hold onto. I smeared my feet and shouldered through the moves. My second try, I sent. Routes of the same grade at the Blasphemy Wall took me months. We left the crag optimistic that the New Year would bring better climbing on our projects.

Soon after, Tilden drove 10 hours south from his home in Lander just for another shot at Necessary Evil. He hiked the boulder problem, grabbed the small pinch and smoothly fell into the slot before walking to the anchors. A few days later, Honnold hadn’t matched his high point, partly because of the typical conditions in the canyon that Leavitt describes as “kind of diabolical.” One day, we’d be freezing, numbing on the tiny holds. The next day would be too hot. The humidity rose and fell, making the holds feel slippery and impossible to grab one minute and perfect the next. On cold days, the wind froze us. On warm days, the wind never came. All the while, the thundering sound of dozens of semis filled the canyon.

Dan Mirsky works Necessary Evil (5.14c)

“I’m going to train in Red Rocks,” Honnold told me a week later. It wasn’t a surprise. He was heading to Patagonia in a week, and his attempts on Necessary Evil had been grim. Even belaying Tilden on the send had done little to motivate him. He’d skipped a few sessions at the Blasphemy Wall to climb in southern Utah at the Chuckwalla Wall. His commitment had been wavering.

“I used to call Necessary Evil the career killer because if you could do it, your name was just added to this list of other good climbers who did this supposed 14c,” Leavitt said, “but for most people, they can’t do it.”

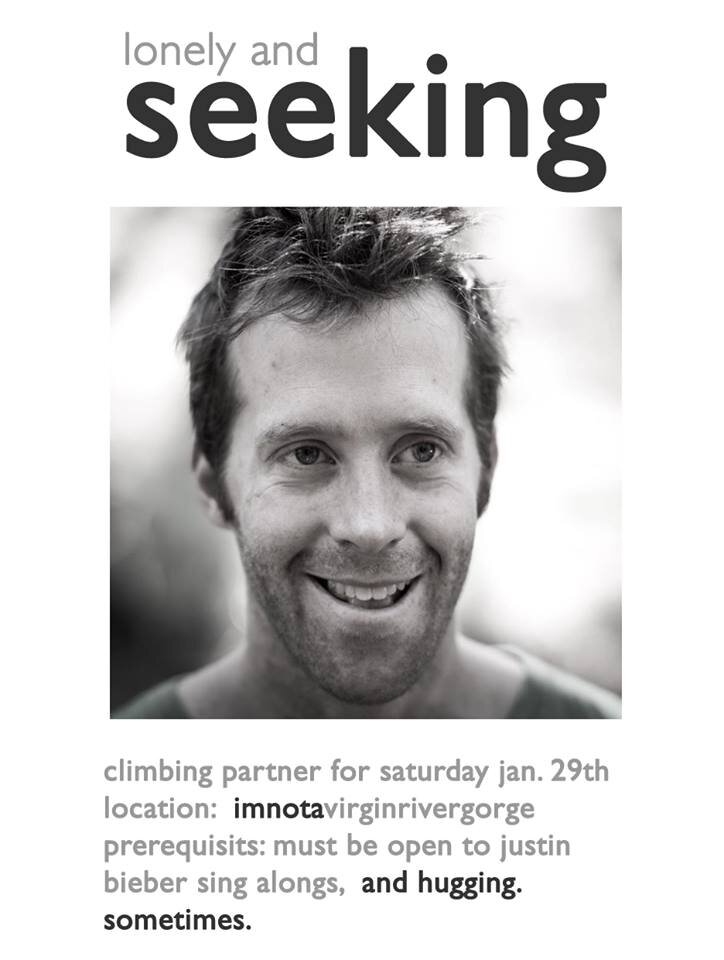

Honnold’s departure left me partnerless. A thoughtful friend put a “lonely and seeking” ad on Facebook to help me find a partner with the prerequisites that they must be open to Justin Bieber sing-alongs and hugging (sometimes). I met climbers from Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, and the Bay Area just to climb a little more. After eight weeks, I had invested so much time into learning to crimp, into Fall of Man, into committing to the runout style. Getting shut down on their projects and escaping for the gym or soft beds at home, my new partners didn’t stay for more than a few days. I drove into the desert, parked by the moonlit Joshua trees a few miles away from the VRG, and cranked Bieber’s “Sorry.” Alone in the BLM land, I scoured the internet for pictures of the VRG, trying to stay psyched.

thanks Tara

On my 34th attempt on Fall of Man, I grabbed a crimp, moved my feet, placed a single finger on an undercling, and threw to a pinch. Finally busting through the hard bottom section, I could still hear the rumbling of the cars on the highway. My legs shook. I felt like an autumn leaf, ready to blow off the wall.

Higher on the route, I grabbed a credit card edge and reached up. I found myself stepping on limestone smears and walking up the low-angle rock. My heart spiked. The space between my ears screamed, completely taxed. Was this it? Would that smear hold? Should I drop my heel? I panicked, took a breath, then stared down to the last bolt 20 feet below, and slowly crept upward. I clipped the anchor and kept climbing until I topped out. I untied and let the cord drop to my belayer. I needed a moment to recover mentally while I walked off the cliff. I wondered what, if anything, was next.

Adrian Ballinger high on the slab of Fall of Man (5.13b)

“I’ve climbed some routes that have so many bolts it’s embarrassing,” Leavitt said. “We never would have wanted something like that at the VRG.” At times, the old-school approach of route development kept people away. The VRG is arguably one of the best sport climbing destinations in the U.S., but the number of visiting climbers pales in comparison to friendlier areas like the Red River Gorge, Rifle, Colorado, or Ten Sleep, Wyoming.

Chris Weidner on I saw Jesus at the Chains (5.13a)

Just to the left of Fall of Man is another VRG classic. I Saw Jesus at the Chains (5.13a) involves thuggy climbing over a roof before sustained crimping for four bolts on a wildly runout slab. “That route had been climbed maybe two or three times in the 20 years since it was put up. That was because there was definitely ground fall potential,” said VRG local Todd Perkins. In 2014, Perkins, funded by Las Vegas climber Rob Jensen, replaced all of the hardware at the VRG with glue-in bolts and fixed perma-draws. Perkins, who lives in nearby St. George, Utah, added two bolts to I Saw Jesus at the Chains, which no one complained about. “We call it sport climbing because that’s what it is. You’re having fun,” said Perkins. “I always believed sport climbing should be something you can pursue safely.”

Emily Harrington climbing on the Blasphemy Wall

The day after completing Fall of Man, one of the hardest routes I’d ever climbed, I sent I Saw Jesus at the Chains. Maybe I was feeling strong, maybe the weather was good, but what probably made the difference was the additional bolts. While this route is still a far cry from a modern, well-protected sport climb, the safer bolting lower on the route allowed me to head into the crux with confidence. I left the VRG shortly after sending, wondering if added bolts enhanced the experience. Whether running it out between protection or fighting through the mental low points, climbing requires commitment.